| Windward Passage All Female Crew | |

|---|---|

The first all-women maxi yacht crew 1988-89: Left to right: 1. Cathy Hawkins 2. Antonia Hawkins 3. Toni Wilkinson 4. Trish Murphy 5. Adrienne Cahalan 6. Andrea Holt (Gus) 7. Karyn Davis 8. Kathy Muir 9. Jenny Ellers 10. Michelle Davis 11. Jody Poe 12. Pip Kyle 13. Susie Kidd 14. Julie Canfield 15. Vanessa Dudley 16. Judy Micklewright 17. Deborah Bowes 18. Chris Evans 19. Susie Green Missing: Susie Allsop, Nicola Bethwaite, Petria Heathwood | |

| Location | Sydney to Newcastle |

| State | NSW |

| Country | Australia |

| Club | Cruising Yacht Club of Australia |

| Year Held From/To | 1989 |

Windward Passage All Female Crew

Crew

Coach: Mike Fletcher

| Number | Confirmed | Position |

| 1 | Kathy Muir | Skipper |

| 2 | Cathy Hawkins | Sailing Master and Helm |

| 3 | Adrienne Cahalan | Traveller Trimmer |

| 4 | Julie Canfield (now Hodder) | Navigator |

| 5 | Nicky Green (Bethwaite) | Helm and Trimmer |

| 6 | Vanessa Dudley | Helm and Trimmer |

| 7 | Susie Allsop (now Allsop-Jones) | Bow |

| 8 | Karyn Davis (now Gojnich) | Headsail Trimmer |

| 9 | Christine Evans | Grinder |

| 10 | Susie Kidd | Mast |

| 11 | Judy Micklewright | Mainsheet trimmer |

| 12 | Andrea Holt (Gus) | Mast |

| 13 | Jodie Poe | Grinder |

| 14 | Toni Wilkinson | Second Bow |

| 15 | Trish Murphy | Grinder |

| 16 | Deborah Bowes | Grinder |

| 17 | Suzanne Green (now Sherwood) | Mast/bow assist |

| 18 | Antonia Hawkins (now Patterson) | Hydraulics |

| 19 | Michelle Davis (now McGrath) | Grinder |

| 20 | Petrea Heathwood (now McCarthy) | Cockpit |

| 21 | Jenny Ellers | |

| 22 | Susie Bell (now Grimes) | Pit |

| 23 | Pip Kyle | Second Bow |

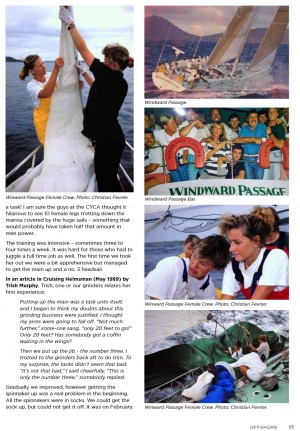

Articles | CYCA Offshore Magazine Spring 2023 - Page 84Windward Passage: First all-Female crew on a Maxi By Julie Hodder Offshore - Spring 2023 by CruisingYachtClubofAustralia - Issuu In the 1980's Cathy Hawkins was a bit of a hero for me. She had competed two handed in the Round Britain Race in the trimaran Twiggy and then came second in the two-handed Bicentennial Around Australia Race on the trimaran Bullfrog (Verbatim). I was invited a few time times to go sailing with her on Bullfrog and was amazed by her skill and tenacity. Cathy then sailed with Kathy Muir off Hawaii. This is when they hatched the idea for an all-female maxi crew on the original classic Windward Passage. So when Cathy Hawkins bumped into me at the MHYC in January 1989 and said: "Kathy Muir and / are looking at putting together an all-female maxi crew on Windward Passage, would you like to join us?", I jumped at the opportunity. Then I was ecstatic to find out I was going to be the navigator aboard. The race was from Sydney to Newcastle (65nm), not far I know, but it was the training and leadup to this race that made it so special. A few of us had sailed on various maxi boats before, however most of the grunt was done by big buffy blokes and usually there was just one female aboard. These maxis at the time were big heavy boats, there were no electric winches for grinding and the sails and other equipment like spinnaker poles were not light as they are nowadays. Plus most of the team had not had any experience on bigger boats so it was a big learning curve for all. But we were all committed. Mike Fletcher (Fletch), also known as "Coach ", was to be our trainer for the next few months. Fletch is a famous Olympic and Admirals Cup coach, and I must say I admire him for taking us lot on. However we did have some famous female sailors on the crew including owner Kathy Muir, co-skipper Cathy Hawkins, Olympians Nicola Bethwaite and Karyn Davis, experienced ocean racer Vanessa Dudley, champion 18'skiff sailing Adrienne Cahalan and rigger Petrea Heathwood from Queensland. Many of us had also done many miles of ocean racing, a few on maxis. At the time Rod and Kathy Muir had 2 Windward Passages, the beautiful classic Windward Passage as well as the new fast Windward Passage II. The "girls" were to sail the classic one which had been substantially re-fitted as an immaculate cruising boat with all the trimmings including , white leather sofas, three private cabins and a vast galley. So we had to be very careful. Such "normal" activities as packing spinnakers were forbidden. That meant once a spinnaker was up it could not be reused again. The "boys" had the new state-of-the art fast 80-footer, Windward Passage II. Our first ordeal was getting to know the boat and for me that was a huge learning curve. The navigation equipment, including the radar, was new to me and there was a bit of resistance from the other side to help us become familiar with it. But luckily, I was a school teacher at the time on holidays, so spent hours reading the manuals to be familiar with all the systems. A big learning curve also for most of the crew was dealing with the much larger equipment. Even getting the sails from the shore to the boat was a task! I am sure the guys at the CYCA thought it hilarious to see 10 female legs trotting down the marina covered by the huge sails - something that would probably have taken half that amount in men power. The training was intensive - sometimes three to four times a week. It was hard for those who had to juggle a full-time job as well. The first time we took her out we were a bit apprehensive but managed to get the main up and a no. 3 headsail. In an article in Cruising Helmsman (May 1989) by Trish Murphy, Trish, one or our grinders relates her first experience:

Gradually we improved, however getting the spinnaker up was a real problem in the beginning. All the spinnakers were in socks. We could get the sock up, but could not get it off. It was on February 14th, yes Valentines Day, that we got our first spinnaker up. We decided to give the sock thing up and just hoist the spinnaker without it. Trouble was we were heading straight towards South Head so the time we got it up we had to gybe immediately, which I may add we executed perfectly. I remember it was pouring with rain that night and we were drenched, but what better way to spend Valentine's nights - I am sure Fletch enjoyed his Valentines Night surrounded by his "girls"! Often in these practice sessions we all had to multitask. I was Navigator, but also had to run under the decks to the bow every time we put up a spinnaker. It took quite a few of us to put the spinnaker pole up. Trish in her article relates her experience:

Our training also included a lot of safety practice. The first time we did a woman overboard drill, Fletcth threw out not only one two "female" fenders for us to retrieve. So his training was really rigorous and something has been imprinted in me. The Sydney to Newcastle race The actual race was basically a night race starting 46 yachts in the middle of March. At one stage it was considered that since Fletch had put so much into our training he should join as an "honorary girl". However, this was quickly ruled out and he sailed up with the "boys" on Windward Passage II. The race was actually a breeze compared with all our training sessions and was sailed in mild east nor'easterly winds, so basically a reach most of the way. Most of the crew were a little disappointed that there was not a lot to do except trying to push our boat as fast as possible. We had watches but as it was just a 65 race, most decided to stay up -too excited to sleep. My orders as navigator included keeping the guy's Windward Passage II boat in sight on the radar. In the beginning there were light breezes, and we not only had the boys in front of us, but the 60' yacht Rager crept in front. The wind gradually strengthened, and our heavier boat picked up speed gradually overtaking her. The end was much more exciting. Trish in her article recalls:

We were second across the line, an hour behind the new Windward Passage II and just seconds in front of Rager. On pulling in at the dock Fletch was waiting to greet us with our boat's T-shirt on. He spent the rest of the weekend enjoying being an "honorary girl", including doing the delivery home. The after party and prizegiving ceremony was held in Newcastle's popular Windward Passage Tavern which had a bar built around the mould used to construct the exotic hull of Windward Passage II. On corrected time. Windward Passage II won the IOR Division while Windward Passage won the Performance Handicap Division. There was a lot of celebrations to be had and one thing us "girls" already knew was how to party. Later that night in the wee hours of the morning, some of us hitched a ride back to our hotel courtesy of the Police in their "Paddy wagon"! A lot of people doubted that we would even make it, but we proved them wrong. We had a lot to celebrate - it was the first time that a maxi yacht had been raced by an all-female crew. |

Training | PicturesThese fantastic pictures of the Windward Passage all female crew were taken by Christian Fevrier (cannot put accent in website), a French photographer. This is some information about Christian Christian Février - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Pictures Christian Fevrier  Heading our for a practice day. Coach Mike Fletch standing up with green shirt  Kathy Muir on helm  Cathy Hawkins on helm  Cathy Hawkins on helm  Cathy Hawkins on helm, Mike Fletcher behind  Vanessa Dudley on helm, Mike Fletcher, Cathy Hawkins and Kathy Muir  Vanessa Dudley on Helm, Mike Fletcher, Antonia Hawkins and Kathy Hawkins  Susie Kidd in foreground, Susan Grimes (previously Bell) on main and Andrea Holt (Gus) in red and white striped shirt  ??, Christine Evans, Susie Kidd, ??? and ????  Jodie Poe on winch sitting next to Judy Micklewright  On the Wind  Christine Evans, ???? and ?????  Nicky Bethwaite on Helm  Nicky Bethwaite on Trim  Nicky Bethwaite on Trim  Nicky Bethwaite and Cathy Hawkins  Susie Allsop (now Allsop-Jones) and Toni Wilkinson hoisting the headsail  It took 5 of us to lift the pole ready for spinnaker hoist  At the mast - need to confirm names  Hoisting the spinnaker was a problem with the sock. From L-R Christine Evans, Andrea Holt, Nicky Bethwaite, Cathy Hawkins and Susan Grimes (previous Bell)  Hoisting the spinnaker cont.  Hoisting the spinnaker cont.  Hoisting the spinnaker cont.  Hoisting the spinnaker cont.  Hoisting the spinnaker cont.  Hoisting the spinnaker cont.  Hoisting the spinnaker cont.  Hoisting the spinnaker cont.  Sailing along with spinnaker up  Spinnaker up - Nicky Bethwaite on Trim  Spinnaker up - Nicky Bethwaite on Trim  Sailing along with Spinnaker up - Christine Evans on grinder  Bow Susie Allsop and Pip Kyle taking headsail down  Grinders - Deborah Bowes on left, Christine Evans to right  Grinders - Deborah Bowes on right, Christine Evans to left  Grinders - Deborah Bowes on left, Christine Evans to right  Grinders - Deborah Bowes on left, Christine Evans to right  Griding the Mainsheet - Judy Micklewright to left.  Andrea Holt (Gus) on trim  Jodie Poe on trim  Andrea Holt (Gus) on trim with Julie Hodder (Formally Canfield) grinding  Vanessa Dudley on mainsheet trim  Dropping the spinnaker  Dropping the spinnaker  Dropping the spinnaker - Suzie Kidd at mast  Dropping the spinnaker  Julie Hodder (Navigator) with old electronic hand bearing compass - very modern for its time.  Julie Hodder (Navigator)  Julie Hodder (right) speaking with Suzie Kidd  Crew Briefing with Fletch  Portrait of Cathy Hawkins (sailing master)  Portrait of Cathy Hawkins (sailing master) |

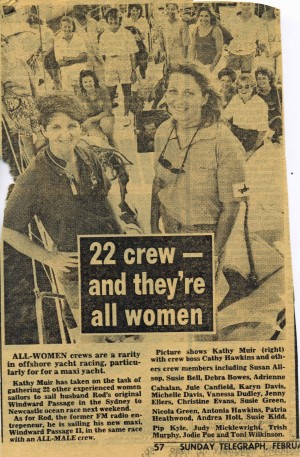

Articles | 22 Crew and they're all WomenALL-WOMEN crews are a rarity in offshore yacht racing, particularly for a maxi yacht. Kathy Muir has taken on the task of gathering 22 other experienced women sailors to sail husband Rod's original Windward Passage in the Sydney to Newcastle ocen race next weekend. As for Rod. the former FM radio entrepreneur, he is sailing his new maxi, Windward Passage II in the same race with an ALL-MALE crew. Picture shows Kathy Muir (right) with crew boss Cathy Hawkins and other crew members including Susan Allsop, Susie Bell, Deborah Bowes, Adrienne Cahalan, Julie Canfield (now Julie Hodder) Karyn Davis, Michelle Davis, Vanessa Dudley, Jenny Ellers, Christine Evans, Susie Green, Nicola Green (or Nicola Bethwaite), Antonia Hawkins, Patria Heathwood, Andrea Holt, Suzie Kidd, Pip Kyle, Judy Micklewright, Trish Murphy, Jodie Poe and Toni Wilkinson. Sunday Telegraph February 12th 1989 Note: We actually took 23

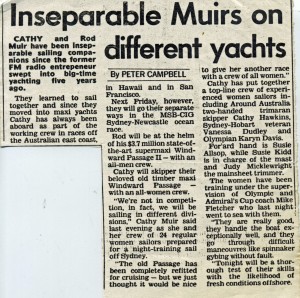

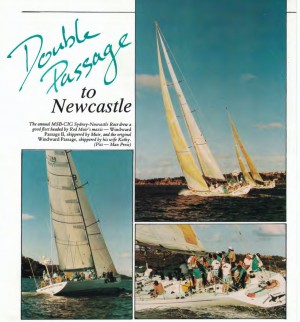

Inseparable Muirs on Different YachtsBy Peter Campbell KATHY and Rod Muir have been inseparable sailing companions since the former FM radio entrepreneur swept Into big-time yachting five years ago. They learned to sail together and since they moved into maxi yachts Cathy has always been aboard as part of the working crew in races off the Australian east coast, in Hawaii and in San Francisco. Next Friday, however, they will go their separate ways in the MSB-CIG Sydney-Newcastle ocean race. Rod will be at the helm of his $3.7 million state-of-the-art supermaxi Windward Passage II - with an all-men crew. Kathy will skipper their beloved old timber maxi Windward Passage - with an all-women crew. "We're not in competition, in fact, we will be sailing in different divisions," Kathy Muir said last evening as she and her crew of 24 regular "women sailors prepared for a night-training sail off Sydney. "The old Passage has been completely refitted for cruising - but we just thought it would be nice to give her another race with a crew of all women." Cathy has put together a top-line crew of experienced women sailors including Around Australia two-handed trimaran skipper Cathy Hawkins, Sydney-Hobart veteran Vanessa Dudley and Olympian Karyn Davis. For'ard hand is Susie Allsop, while Susie Kidd is in charge of the mast and Judy Micklewright the mainsheet trimmer. The women have been training under the supervision of Olympic and Admiral's Cup coach Mike Fletcher who last night , went to sea with them. "They are really good, they handle the boat exceptionally well, and they go through difficult maneouvres like spinnaker gybing without fault." "Tonight will be a thorough test of their skills with the likelihood of fresh conditions offshore. Other Pictures Julie Hodder (then Julie Canfield) on deck  Both Windward Passages  Windward Passage Crew in Race Mode - Julie Hodder on helm  Kathy Muir Picture that was signed by crew and presented to her  Old contact list Double Passage to NewcastleCYCA Offshore Magasine April 1989 INTRODUCED in 1988 as part of the aquatic celebrations for the Bicentenary, the Sydney to Newcastle Race has become part of the Cruising Yacht Club of Australia's offshore programme, bringing with it the enjoyment of a fast overnight passage race to a different port and the subsequent social activities ashore at the finish. The second event, in mid-February, again attracted the support of the Maritime Services Board and sponsorship from CIG, along with enthusiastic support ashore and afloat from maxi yacht owner and developer, Rod Muir. Muir not only entered his two maxi yachts, the timber-hulled 20-year-old 72-footer Windward Passage, and his state-of-the-art new 8O-footer, Windward Passage II, but he also turned on a magnificent post-race party for the visiting yachties. This was held in the Windward Passage Tavern, a bar built around the mould used to construct the exotic hull of Windward Passage II. Muir had good reason to lead the celebrations around the port of Newcastle, his two maxis took line honours in their respective divisions and they also won on corrected time. Muir, skippering Windward Passage II, sailing her first overnight race since the setback in the Sydney-Hobart, took line honours in the time of 6 hours 58 minutes 52 seconds but only an hour ahead of the veteran Windward Passage - skippered by his wife, Kathy, and sailed by a crew of all women. The old boat, refitted for cruising after a long and illustrious international racing career, was superbly sailed by Kathy Muir and her crew, which included Around Australia Race co-skipper Cathy Hawkins, Olympian Nicola Green and experienced ocean racing helms woman Vanessa Dudley. In a boat-for-boat dual up the coast: Windward Passage beat the fast 60-footer Rager across the line by seconds. On corrected time, Windward Passage II won the IOR Division while Windward Passage won the Performance Handicap Division in what must have been an historic result in yachting. Sailed in mild east nor'easterly winds, the MSB/CIG race a:ttrac;ted a fleet of 46 yachts. Race conditions were ideal, just one yacht, Chloe, failed to finish the event. Second to Windward Passage II in the prestigious IOR category for grand prix race yachts was Warren Johns on Beyond Thunderdome, trailed by Max Ryan's Venture I which crossed the start line early and was forced to circle back through the fleet. Ocean Blue Resorts sailed by Graeme Lambert, took fourth in the IOR Division from Swuzzlebubble Six, the ex New Zealand Southern Cross Team yacht now sailed by Sydney's Colin Boyle and Nadia IV, owned by the Canberra based author, Teki Dalton. In Division II of the IOR fleet, John Eyles' Indian Pacific took the honours from Ray Stone in Middle Harbour Express and Invader sailed by Eric Stano.

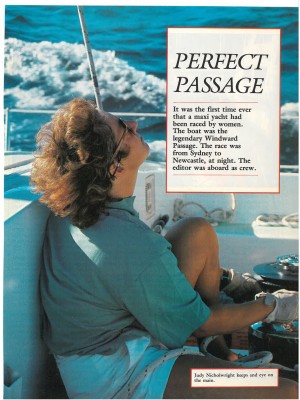

PERFECT PASSAGE Perfect Passage Page 1 Judy Nicholwright keeps and eye on the main  Perfect Passage Page 2  Perfect Passage Page 3  Perfect Passage Page 4  Perfect Passage Page 4  Perfect Passage Page 4 Cruising Helmsman May 1989 by Trish Murphy (one of the crew) It was the first time ever that a maxi yacht had been raced by women. The boat was the legendary Windward Passage. The race was from Sydney to Newcastle, at night. The editor was aboard as crew. I was wandering down the corridor towards the front door of the Cruising Yacht Club of Australia when somebody coming the other way stopped me. "Are you one of those girls?" he said. "There's a message for one of those girls." "Huh? Who?" He looked exasperated. "Which boat are you off?" he said. "Windward Passage," I replied. As I did so, I suddenly wondered how many people, all over the world, down the long time-corridor of 20 years, had answered the same question with those same words. Windward Passage. The body of water for which she is named lies in the Caribbean, between Cuba and Haiti, north-east of Jamaica. Passage herself has sailed all the waters of the world in her 20 year life-time, competing in the world's more exotic races, winning for herself a reputation that extends far beyond the sum of her parts as simply a boat. When Rod Muir bought Passage, she was at the scruffy end of a long career. She was sent to New Zealand, where for 18 months she was substantially re-fitted. The result: a fabulously finished cruising boat with immaculate spruce veneer on her hull, white leather sofas, three private cabins, a vast galley. Her deck had been altered, too, and in fact areas of it proved quite difficult to work, with foot chocks removed and nowhere to hang on to. That afternoon wandering through the CYC, I had just bid farewell to the boat. We had brought Passage home from her last race. And although for her, it was a final event, for us, the crew who sailed her, it was a first - in more ways than one. It was the first time ever that a maxi-yacht has been raced by an all-women crew. For many of us, as well, it was the first time we had ever sailed a maxi at all. It was a chance not to be missed, and it came with a phone call from Cathy Hawkins, who had recently completed the Around Australia Race on the trimaran Verbatim. While sailing off Hawaii, she explained, she and Kathy Muir had hatched the idea together. Was I interested? The rationale behind the idea extended further than just a boat race. Although Passage had cruised a considerable distance since her refit, she hadn't been raced. Nor, in her new form, was she intended to be raced. However, racing a boat is by far the best (and the most quick) way to discover her weak points and stress areas. Kathy Muir explained later that she felt that 23 women on board would be more sympathetic than 23 men. I hope we were! On asking who else was to be aboard, I discovered I was to be in experience company. Besides Cathy Hawkins, Kathy Muir (who crews aboard her husband's new boat, Windward Passage II), there were to be Olympians Niki Green and Karen Davis, skiff sailors Vanessa Dudley and Adrienne Cahalan, rigger Petrea Heathwood from Queensland - it was a long list. Our coach was to be Olympic and Admirals Cup coach Mike Fletcher. Our first day on the boat was a little bewildering. There were names to match to faces, positions to be allocated, techniques to be learned. Beneath our feet, Passage waited patiently. This was a dry run - we didn't take her out of the pen. She seemed awfully large - all her winches, blocks, sheets looked (to me at least) absolutely huge. To clip the main halyard on to the headboard, some-one had to scramble 20 feet up the mast. Cathy suggested I familiarise myself with the coffee grinders. I fiddled with them, but didn't pay too much attention. I was sure that a group of super-fit aerobics types would be shipped in for this job. Being an office lizard with an aversion to exercise, I could barely make it to the cigarette machine without flagging. But towards the end of that first meeting, I hadn't been given a position. On accosting Cathy, she said that Fletch would allocate a position. For a minute she looked half apologetic, half hopeful: "You are very strong," she suggested. On deck, I took another look at the crew and came to terms with the fact that at mix foot, I was definitely the largest member of the company. That could only really mean one thing. With a degree of dread, I began to pay better attention to those grinders. In John Bertrand's book about the Americas Cup, Born To Win, there is quite a lot about grinding. In particular, I remembered the tacking duel of the last race in 1983, where after 48 or so tacks, the grinders went into the "red zone" -where physically, they were in danger of having heart attacks and things. They called each tack for a member of the crew to give themselves the strength to get through it. I wondered if this was a good time in my life to give up keel boats and take to boardsailing or something. If it were any other boat but Windward Passageâ¦. The next time on the boat, we took her out. Putting up the main was a task unto itself, and I began to think my doubts about this grinding business were justified. I thought my arms were going to fall off. "Not much further," some-one sang, "only 20 feet to go!" Only 20 feet? Has somebody got a coffin waiting in the wings? Then we put up the jib - the number three. I trotted to the grinders back aft to do trim. To my surprise, the tacks didn't seem that bad. Mike Fletcher had the task of turning 23 individuals into a working team. He moved about the boat quietly talking to different people in different positions. Back aft, he advised us of how best to master the grinding. Basically, you go like the clappers to get as much line in as possible before the jib loads up. "It's not that bad," I said cheerfully. "This is only the number three," somebody replied. The next time out, we put up the number one. It's a big, big sail - Passage has a masthead rig. On the third tack with that sail, I was not so much worried I would die as worried that I wouldn't. Then I seemed to break into a second wind, and began to enjoy the sailing. We began training three and sometimes four times a week. It was often hard going - most of us had full-time jobs, and a bad day at the office would interfere with our concentration on the boat. Eventually the office was put on hold, and anything that needed to be done had to wait till "after the race" . On sailing days I smoked less and ate a lot of pasta. Not everybody could make it to every session - some days were five or six people short. That meant hard work all round. Chris Evans and myself worked the for'ard grinders, and we'd be on the trot most of the time. We would put up the main and headsail; run aft to help trim, run for'ard to grind up a new headsail, run even further for'ard to help get the old one down and lash the beast to the deck, run aft to trim. Kite sets were even more frenetic. I would find myself willing the wind to blow hard on sailing days, so that we could set the number three rather than the number one. Jody Poe and Susie Bell on the main-sheet grinders tended to disagree - they preferred light air for their job. Some days were invigorating, others demoralising. Two weeks into training, Kathy Muir said that Rod would be aboard for that week's twilight race. That was a little bit of pressure for us, as we wanted to sail the boat well. It was not a good day, however. A decision to change headsails for a downwind leg, and a reluctance to change back for the beat, led to disaster. We were grinding through the tack when we heard an ominous cracking noise, and the trimmer yelled to us to stop. Now, with the number one, if it became fouled as it crossed the centre of the boat, it meant a lot of grinding for us to bring it in. So I was grumbling as I turned my head to see what the problem was. What I saw were little flags of kevlar flogging furiously in the wind. I don't remember running up the boat, but I do remember pulling the leechline down, incredulous. How did it happen? We put up the number three and kept going. Fletch said the sail could probably be repaired. A combination of things had caused the blow-out. The tack had been faster than usual. There was too much wind for the sail. It had caught on the spreader as it went through. __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ The Race I warned the office in advance that on the day of the race, I would be Out. It was a night race, starting at 5pm, so that morning I did my best to sleep late. I was too excited, however, and set off to find some white shorts and put myself through the pre-grind ritual of eating as much as possible. We set up the boat, stopped the spinnakers and sailed out at 3.30 to have a look beyond the Beads and warm up. Cathy Hawkins talked about the weather. Twelve to 14 knots from the east, and a relatively flat sea. We'd sail all the way up on a reach, which was Passage's best point of sail. We couldn't have asked for better. The breeze would probably fade around 9pm, and the two hours between 9pm and 1 1pm would be critical for us. We would head out a little way around then, to catch the last of the breeze. The southerly set had in fact shifted a little way offshore, and should not be a problem. The start was a very calm affair. We picked the leeward end of the line, choosing to avoid the press of boats jostling to windward of Shark Island. Passage II crossed our bow, tacked and sped away in front of us. I was mortified, through - out this process, to discover that as we had, full crew, the aft grinders were well staffed, and all I had to do was sit on the rail. Once we'd turned left at the Heads, we put up the staysail and there was some adjusting of the jib. Move the foot outboard, no, a bit further, is that working? There was much leading and re-leading of sheets. During this time Rager - the opposition - passed us. They waved us goodbye. Eventually we took the staysail back down again, put the jib back to where it was in the first place, and settled down. The breeze was soft - nine knots. Rager loved it, but we couldn't really get Passage up and running in less than 10 knots. A little later in the evening, the breeze strengthened, and we steadily closed on Rager's stern. About then, things on our boat became rather quiet. We held our breath, the breeze remained steady, and we finally gained the lead over the other boat. We kept it for the rest of the race. Sailing on only one tack for the entire distance left little in the way of work for many of us. We lounged around, ate dinner, kept a lookout for Rager's nav lights. A short watch system was introduced, and some went below for a nap. I stayed on deck. At one point, lounging aft with my shoulders wedged between the backstay and the radar post, I drowsed off. I thought that this was what it must feel like to sleep in the fork of a tree. Why would one sleep up a tree? Because one was in Africa, of course, and there would be lions on the prowl. But lions can climb trees. A lion was pawing at the trunk of my tree, and - bloody hell! Someone had stumbled over me, waking me up. I took a minute to figure out that I was not up a tree in Africa, but on a large boat in the Tasman. Then the trimmer called us to grind in a bit of sheet. Turning towards Newcastle, there was debate as to whether or not we should set the kite on the run over the finish line. There was some consideration of sea room, and we thought we might pole out the jib. Niki Green, who had been below during the debate, came up on deck and initiated a kite set anyway. A good thing too. Rager's sails were ghosting along the other side of the breakwater. She had cut the corner and halved our lead over her. Had we not set, she might well have beaten us over the line. But we did set. Then there was talk of a gybe. Preparations for a gybe began, but a voice (don't know who it was) yelled from the middle of the boat: "Why gybe if we don't have to?" We didn't gybe, and I heard a gun as we crossed the line. In the rush of drop-ping sails and coiling sheets, somebody mentioned that we had quite a good handicap for age allowance. I don't know if, when we began the whole operation of sailing Passage, we had thought much about winning. The plan was to get there with no dramas. We had been warned by Rod Muir that if we beat his new boat, we should not go to Newcastle, certainly not tie up at the dock. "Just keep going," he warned, with a big grin on his face. Fortunately, the new boat arrived a good hour ahead of us, winning its own division. We had taken line honours in our division. We found out the following day that we had won it on handicap as well. The Windward Passage Tavern on the Newcastle waterfront is an airy oasis amid the last traces of an earlier, more grimy era. Centrepiece of the bar is the plug for Windward Passage II, all dressed up to look like the boat itself, and wearing mast and boom, and orca on the stern. That night, when we finished the race (I was told), Fletch, who had sailed up on Passage II, had been keeping watch from one of the tavern terraces. When he saw us coming down under kite, he apparently yelled: "It's my girls!" and bolted for the dockside. He spent the remainder of the weekend wearing a Passage T-shirt and joked more than once that he was proud to be "an honorary girl". We loved him for it. In the bar that night, things were heady. Bets had been won and lost. The various Passage II boys who had been betting on how far we would/wouldn't make it up the coast (two miles/four miles/six miles) had lost out. Somebody grabbed me near the entrance and yelled at me: "Fantastic! Amazing! You actually made it!" "Well the conditions weren't very difficult," I said. "Yes, but you actually got here! Incredible!" "Well what did you expect? That we'd sink the thing?" _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ The Trip Back In Newcastle, we had a day to consider things before sailing Passage home again on Sunday. Naturally, we spent a fair bit of time celebrating. One or two crew said that although we had had a great sail, we had had little cause to use our new maxi skills. The sail home gave us that opportunity. On Sunday morning, there was word of a front moving up from the south. It was at Montague Island, travelling at 20 knots and with 25 to 30 knots behind it. , Many crew had returned to Sydney and elsewhere by train, and others had brought friends aboard. Fletch, who had been standing on Passage II with his yellow bag, jumped off their ship and on to ours. We were ready to leave, he explained to them, while they were not. "Anyway," he said, "it's better company on this boat." We motor sailed in light air for several hours. It was sunny and hot, and we lazed about the deck, trying to ignore the whap-whap of the slatting main (who said fully-battened mains don't flog?). Eventually, however, a dark band of cloud began marching towards us. We put up the number four, reefed the main, cleared away the spinnaker sheets and made sure Passage was snug. The breeze filled in steadily from the south, until it was puffing 20 to 25 knots. It was then that we really had a taste of maxi sailing. Kathy Muir had once warned us that Passage was a wet boat. Wet was probably a euphemism. Sitting up along the windward gunwale, we were doused time and time again with sheets of water. People working up around the bow and mast began to look thoroughly bedraggled. When the decision was made to put up the staysail and drop the number four, I went up for'ard to help. Up on the bow, wedged between the staysail and the safety lines and trying to lash the number four to the deck, there was so much water and salt in my eyes that I couldn't see anything at all, and was working blind. Just as soon as I'd blink it away and grab a quick look at what was going on, whoosh, we'd be drenched again. I thought it was fun, but then I knew that within a matter of hours we'd be home and dry. Sailing the Whitbread, for example, would be a completely different kettle of fish. We sailed past Barrenjoey, which suddenly looked unfamiliar and strange in the grey afternoon. I've passed it often before, and yet this time it didn't look like Barrenjoey at all. A long tack out and another back in, and we were bang in line with North Head. Heading out on the race, the water around North Head had been dark, sickly brown and foul-smelling because of the effluent pumped out there. With so much water coming over the bow now, I hoped the wind had blown the worst of it away. In the harbour we started the motor and dropped the sails, but then discovered that the motor wouldn't engage. Carson, the boat's caretaker, reported that all the bolts in. the coupling had dropped out. We sailed up and down under staysail while he fixed it. And finally, I was standing in the draughty corridor of the CYC. "Are you one of those girls?" the man was asking me. "Yes, yes I am. Problem?" "Oh no," he said, "just a message. It says, good on you." I thanked him, and went home Some Larger images from Cruising Helmsman Story Skiffie Vanessa Dudley was a trimmer and also took her turn at the helm  Centre: Chris Evans and Lynne -Lynne was press-ganged into helping when we were short of crew, although she did not sail the race.  Susie Kidd doing her job at the mast  Cathy Muir on the helm, Chris Evans at the hatch  Pip Kyle enjoying a rare quiet moment during racing  Sail Detail required a platoon of crew - this one was only the number 4  Windward Passage "Girls" The first all-women maxi yacht crew Photo 1989: Left to right:

Missing: Susie Allsop (now Allsop-Jones), Nicola Green (Bethwaite), Petra Heathwood (now McCarthy), Susie Bell (now Grimes). Celebrations at Windward Passage Bar Newcastle |